The biotech sector has embraced the microbiome in recent years, a green field market powered by cheap genome sequencing and venture dollars, promising bespoke treatments for everything from gut troubles to skin problems. But a report in Science alleges that these companies lack scientific rigor and meaningful regulation, offering little more than guesswork on a complex and understudied area of human health. The startups in question offer a nuanced response to this criticism that emphasizes their efforts to achieve legitimacy in an area they admit has the potential for snake oil.

The microbiome is a general term for the unique mix of bacteria and other microorganisms that each of us has in and on our bodies. Your skin, gut, mouth, genitals, and any number of other parts have a rich variety of resident life, from those thought to be longstanding and beneficial to newer, rarer, or even “invasive” ones.

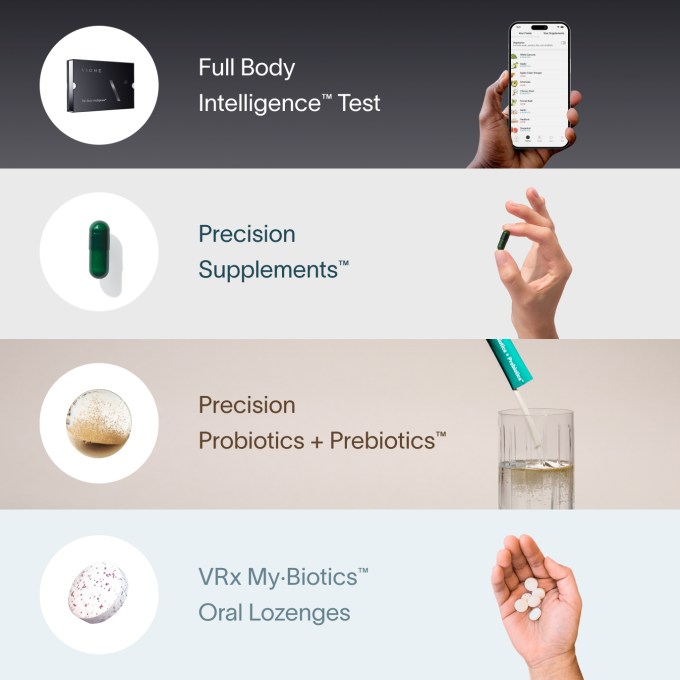

What many companies have proposed is that by profiling one’s microbiome, many related health problems or benefits can be identified, treated, or promoted. This profiling is accomplished by mass genomic analysis of a swab, stool sample, or some other biological source, a process that (the companies say) quantifies the good, bad, and ugly life endemic to your body.

But six scholars, citing a variety of researchers, clinicians, patients, and other experts they interviewed, warn against what they see as a largely unregulated industry rife with snake oil. (This is not a peer-reviewed research paper, but still relies on original research.)

“These companies claim they can determine whether a customer’s microbiome is healthy or in ‘dysbiosis’ — out of balance — and suggest that if so, it could be the reason for one or more health problems,” the group writes. “Some of these companies may knowingly mislead consumers, while most appear to engage in questionable practices that are permitted by gaps in the current regulatory framework.”

The problem is not with the idea of microbiome profiling in itself. As microbiologists and researchers on microbiome issues, they are well aware of the potential for, say, an abnormal gut microbiome to contribute to any number of health problems. The scientists — and entrepreneurs — that I’ve talked to all agree that this is a potentially transformative area of research and medicine that has only in the last decade become practical to study at scale.

This is because the price of analyzing genetic materials has dropped through the floor, while the ease of handling the large and complicated dataset that results from such testing has risen equally fast. The result is an embarrassment of data, in which could very well be hidden a treatment path for many a person’s health issues.

Where the authors take issue is with the presentation of microbiome profiling and treatment as established science and the lack of regulation that prevents them from making these claims.

“Many of their marketing claims imply, and may lead consumers to believe, that the results are grounded in scientific accuracy and are medically relevant when that has not been substantiated,” they write.

Although many companies tout studies, these are often internally performed and, because they are based on proprietary data, difficult if not impossible to replicate.

Viome, for instance, which raised $86 million last year, cites a study supporting its claim that its service can help people with their irritable bowel syndrome, depression, and diabetes. I lack the expertise to evaluate the study, but it and others like it are all by Viome employees, on Viome data, using Viome methods. Though it appeared in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, it has not (like many papers, to be sure) been cited except by subsequent Viome studies. (I asked Viome for comment on the arguments of the Science piece, but did not hear back as I did from the others.)

It’s up to you and your doctor to decide if this is sufficient scientific backing for a nutrition-based approach to treating your diabetes. But the Science piece’s authors assert that all these studies are conducted on shaky grounds, because there is simply no accepted, foundational understanding of microbiomes and their effects on any bodily processes whatsoever.

“The companies need consistency in processes and methods to ensure consistency across labs, but they also need reference standards with which to compare their results and make sure if they say a consumer’s results are within a ‘normal’ range, they are in fact consistent with what would be a ‘normal’ range,” co-author Dianne Hoffman, of the University of Maryland, told TechCrunch. “That has not as yet been established.”

“There is no consensus about what constitutes a healthy human microbiome composition in any population or subpopulation,” the report states.

Yet microbiome companies tell users not just what is or isn’t healthy, but also what they can do — and buy — to improve it. Nearly half the companies surveyed by the authors sell the supplements they recommend, and of course recommend you do a few follow-up tests on their platform to track their effects.

Viome’s front-page testing-through-supplements pitch. Image Credits: Viome

Even if there were that foundational knowledge, the authors point out that the testing processes used by microbiome companies “have been shown to lack analytical validity, resulting in inconsistent test results from the same sample across different laboratories as well as within the same laboratory.” This is not a blanket statement that they are inaccurate or that there is nothing companies can do to mitigate the tests’ shortcomings, but that there is no standard and no requirement to do so.

The FDA, they note, does not regulate these companies, since each is careful about the extent and wording of their claims and don’t say that, for example, their supplements are a full-on treatment for a disease. Instead, they may be described as improving outcomes, or advancing holistic well-being, or anything else you might find on the packaging of a supplement.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) nominally regulate them, because their labs must be run within certain legal limits. But as the authors point out, microbiome testing falls between the cracks because it is not intended to find a particular pathogen or level. They can get CMS certification without showing evidence that their tests are accurate. Again, this is no guarantee that they are inaccurate, but one must admit it is troubling to hear that so little is apparently required of them.

But one may also ask, what is wrong with someone getting more information and taking a supplement that, like so many, is at worst ineffective rather than actively harmful? The report cites a risk of “self-misdiagnosis, delay in seeking medical treatment, and substituting nonmedical supplements for prescription medications.”

“There are patients with chronic gut illnesses, including children whose parents are searching for cures for their children, who are following nutritional or supplement recommendations that are actually harmful to them. One physician we heard from shared that he has heard of patients doing a DIY fecal microbiota transplant on the basis of the results from a DTC microbiome based test,” co-author Diane Hoffman told TechCrunch.

Startups call criticism fair for some, but not for all

The report is unsparing in its criticism of this corner of the industry, but it paints with a broad brush and by necessity does not delve into specific cases. I asked the leaders of three companies that provide microbiome testing for various reasons what they think of the assertions made in the report above.

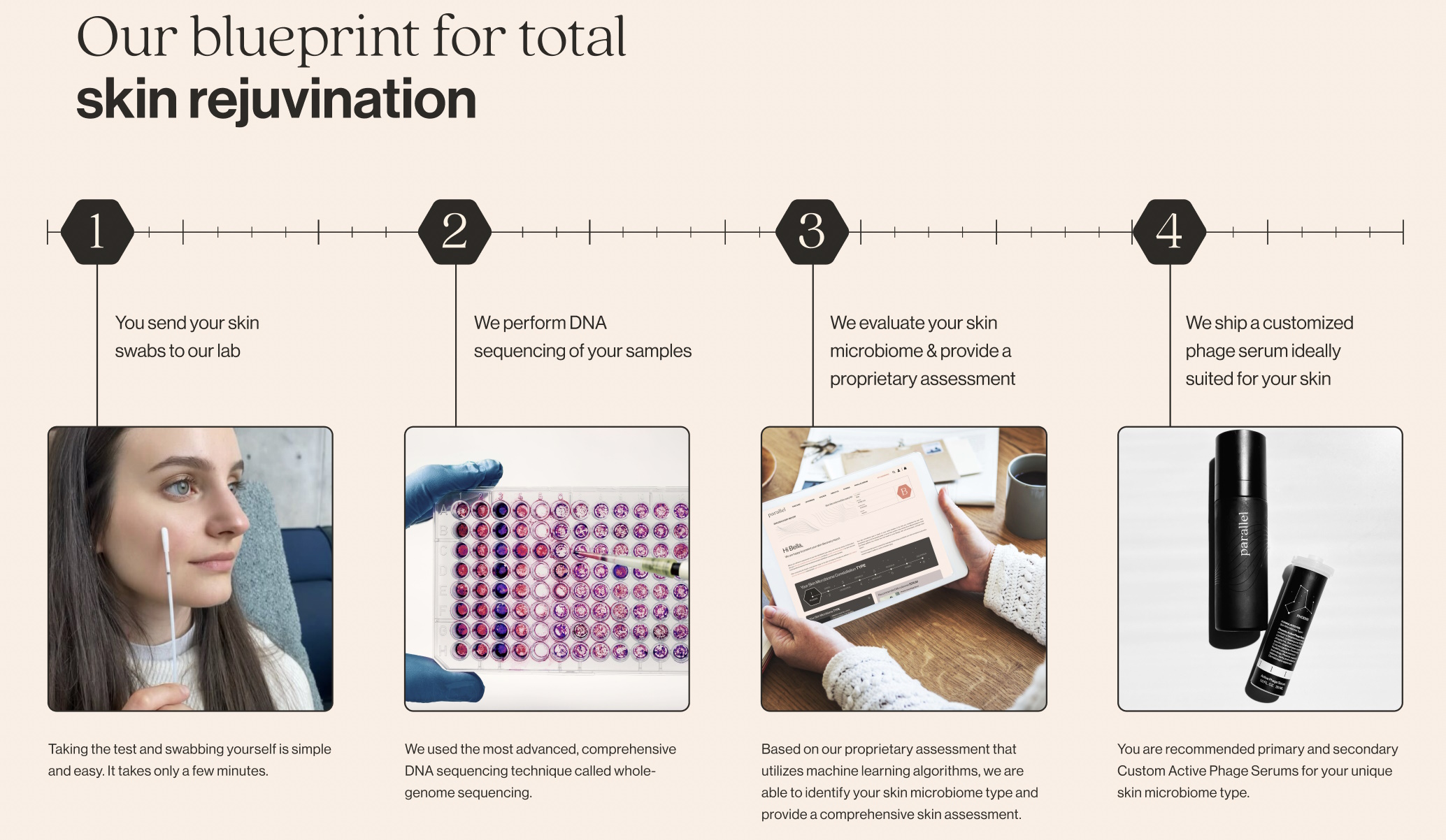

Natalise Kalea Robinson, co-founder and CEO of Parallel Health, which provides phage-based treatments catering to a customer’s skin microbiome, actually agreed with many of the points, making it clear that it is up to the company to do better.

“Concerns around analytical validity are warranted,” she said. “This challenge is not only relevant to DTC microbiome companies but to all next-generation diagnostics companies at large. When you have technology advancing at the speed that it is, especially spurred by AI, it is hard for regulators to keep up. There is a very real and important hunger among consumers, and within at least some part of the microbiome industry, to finally develop a clinically validated human microbiome test. That we do not have one already is not a failure of regulation, but a lack of ambition in the microbiome industry.”

Image Credits: Parallel Health

The challenge, she said, is that the amount of data needed to produce a clinically validated, FDA-approved microbiome test means it can’t be collected without a company like hers doing so as a business. She agreed that there is little consensus on what constitutes a “healthy” microbiome and that, as a result, they had to use all of their initial funding to build a broad, diverse dataset that would serve as one for their purposes. (This is still proprietary, internal data, a worry from the report.)

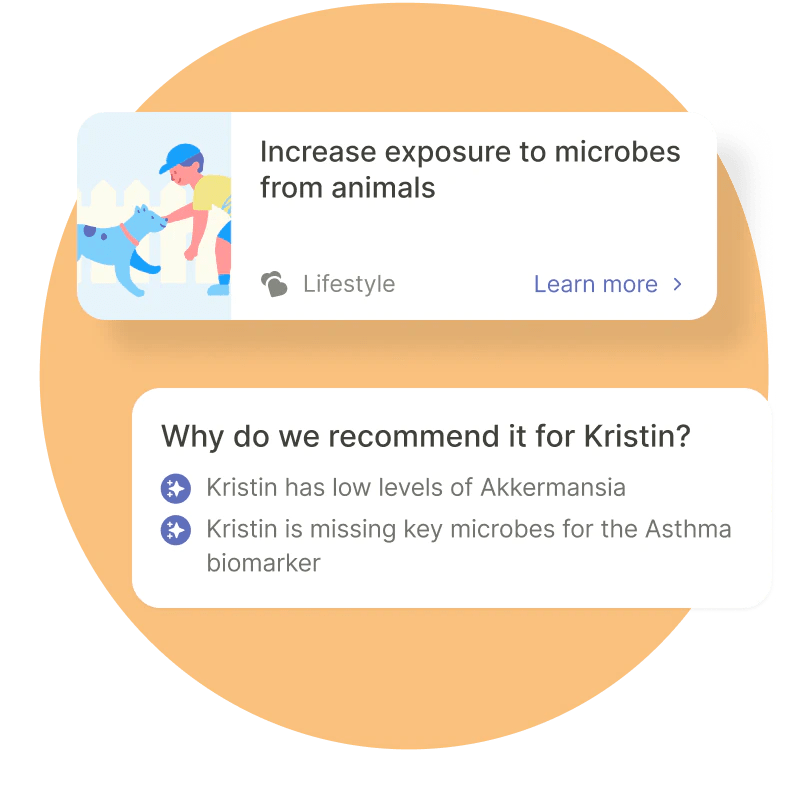

Cheryl Sew Hoy, founder and CEO of Tiny Health, focusing on pediatric microbiome data, was quick to point out that while there may be no scientific consensus on adult gut health, there certainly is one for babies.

Image Credits: Tiny Health

“Because there are so few microbes in the early days — and the only function of the infant gut in the first 6 months is universally to digest milk and not a diversity of food — it’s much easier from a scientific perspective to characterize what is healthy or unhealthy in an infant’s gut, which is what Tiny Health specializes in,” she explained. “For that reason, the infant gut in the first 1,000 days is also much more malleable, only stabilizing after 3 years of age. Therefore, there’s much more scientific validation of what constitutes a healthy development of the infant’s immune system, which is intrinsically tied to the infant’s gut development.”

She said that the company does not diagnose, cure or treat any conditions or provide medical advice. This may be strictly true, but it must be said that it does offer to “prevent or manage microbiome-related conditions like colic, eczema, food allergies, asthma, constipation and more,” admittedly with the support of a doctor, but some recommendations, like exposure to pets, are made in-app. So although they are doing the right thing, they are also flying fairly close to the sun in that sense.

That said, Tiny Health is also laying the foundation for becoming an FDA-approved diagnostic and treatment platform, running a pair of clinical studies tracking how their reports and recommendations affect a child’s first 1,000 days. Sew Hoy also said that they are improving outcome tracking with strain identification, so you can tell if a particular probiotic is working (that industry, she noted, is “currently the wild wild west and not all companies/products are created equal).

Daye is a microbiome startup focusing on women’s reproductive and sexual health, and founder Valentina Milanova was quick to set her company apart from others (not just because it also has to comply with U.K. health regulations).

“In the US D2C landscape, the vaginal microbiome is traditionally tested with gene sequencing technologies, which have limitations, when it comes to the standardization and validation of the method. These technologies also identify a number of microorganisms that are largely under-researched and with unknown clinical utility,” she pointed out. Daye, on the other hand, uses a PCR test that identifies only a subset of known, clinically significant microorganisms. PCR testing also has a more robust validation and quality control system.

Milanova did not disagree that some microbiomes are under-documented, but said the vaginal microbiome is not one of them. “There is a scientific consensus on what constitutes a healthy vaginal microbiome — one that is dominated by lactobacilli bacteria. These produce lactic acid and other antimicrobial substances that maintain a protective vaginal pH and inhibit opportunistic bacteria from growing and causing infection,” she wrote.

“Daye’s test enables us to measure the relative abundance of good bacteria, as well as that of opportunistic microorganisms, that cause BV and yeast infections when found in large amounts,” she continued, but this is only one step in a clinician-involved process that must identify the specific pathogen before recommending a treatment. In the U.K., this can be done within Daye’s platform, but in the U.S., they work with a network of clinicians.

She also shared Kalea Robinson’s perspective that venture funding is “an imperfect mechanism for funding R&D and innovation … venture capital investors operate on a short timeline and venture-backed startups need to provide commercial results in timelines, which are often unreasonable for medical innovation.” They use grants and regular income as well to support this important work.

As far as regulation, all three women said they welcome it, as it should help ensure consistent and helpful outcomes.

“We hope that the FDA will recognize that microbiome tests can help improve health outcomes if done right,” Kalea Robinson said. She expects its authority to expand and include their work sooner or later, and to that end “we are doing the hard work now” to prepare for that.

For those that aren’t, the sense is that regulation is needed to curtail this nascent and disorganized industry’s equivalent of invasive and opportunistic microorganisms — even the well-funded ones.